Aboriginal Heritage

Churchill Island was ‘home country” to the Boonwurrung/Bunurong people, an Aboriginal tribe whose traditional lands ranged from south of the Yarra river in Melbourne to the Tarwin river in South Gippsland. The land and sea visible from Churchill Island are the tribal lands of the Yallok Bulluk clan. Churchill Island was known as Moonar’mia and as a place of special significance that has a legend associated with the Moonah tree. Lt. Grant did not record meeting Boonwurrung/Bunurong people during his time in Western Port in 1801; he did however notice signs of their presence such as remains of canoes and remains of fires.

An Aboriginal midden on the eastern coast of Churchill Island has recently been identified by an archaeological survey as part of preparation of the Churchill Island Conservation Management Plan.

Churchill Island’s Historical Significance

Located north of Phillip Island in Western Port, Churchill Island was walked on by Boonwurrung/Bunurong Aboriginal people and has an important place in the history of the settlement by Europeans in Victoria.

Following the exploration and naming of Western Port by George Bass in 1798, Lt James Grant disembarked onto Churchill Island from the Lady Nelson in March 1801. He named this small island after the man who had given him seeds to bring on his long journey.

Here trees were felled to enable the building of a blockhouse and the seeds were planted making it the site of the first European agricultural pursuits in Victoria.Since the 1850s, this fertile, 57 hectare island has been continuously farmed and in 1872 when Samuel Amess, former mayor of Melbourne, purchased the island for both holiday and farming use, he built a substantial house and outbuildings. Largely intact today, these include two cottages that have evolved over the years from the 1860s and are part of the historic precinct.

In the garden is the cannon which is believed to have been given to Samuel Amess by his friend and neighbour from nearby Cape Woolamai, Captain John Cleeland. Together, the buildings and garden reflect the lifestyle and farming methods of the 19th century.

As a holiday house of the 1870s, the timber homestead is of particular importance. Original wallpapers and internal finishes that have been uncovered provide valuable evidence of contemporary interior decoration. Today, the house is presented for public viewing, furnished and decorated in the spirit of the time.

The landscape of Churchill Island has been classified by the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) and now that Churchill Island belongs to the people of Victoria, we are all welcome to study and enjoy its natural characteristics. These include the unique and ancient Moonah trees and an abundance of waterfowl, sea birds and migratory wading birds. The whole island is also registered on the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) H1614.

The entire area of Western Port surrounding the island has been listed under the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, (the RAMSAR Convention).

An Aboriginal midden and archaeological remains of stone foundations (HVR H7921-0014) contribute to the historic and cultural importance of this unique island. The presentation of early farming methods and a 19th century homestead surrounded by a garden that contains trees planted during the Samuel Amess era – including a Norfolk Island Pine gifted to Amess by Ferdinand von Mueller and planted to commemorate the building of the house in 1872 – give a valuable insight into the social history of Victoria.

Exploration of Churchill Island

Material from:

Narrative of a Voyage of Discovery

Performed in His Majesty’s Vessel The Lady Nelson

1800-1802

James Grant, Lieutenant in the Royal Navy

Some information is taken from the

Logbooks of the Lady Nelson by Ida Lee (1915)

available at http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks/e00066.html#ch06 and Wikipedia biography of John Murray.

Summary by David Maunders

The Churchill Island Museum has two copies of a reprint edition of Grant’s journal originally published in 1803. Parts of Grant’s journal have given us information about his stay on Churchill Island, building the blockhouse, planting the seeds given by Devonshire Farmer Churchill in 1801 and naming the island. The journal gives great detail about many other aspects of Grant’s voyages and it is of interest of provide a brief summary of some of the major events in order to put this voyage into context.

Grant begins with a long discourse on the origin of sliding keels and their advantages. Anyone who has sailed centre-board dinghies in the last half century or more would be familiar with the principle but for Grant is was something quite new. The sliding keels were two or three large boards which could be raised or lowered. The inventor was Captain Schanck during the American War of Independence for vessels in the Great Lakes. Vessels could be built flat-bottomed with little draft but would hold course into the wind when the keels were lowered. The Lady Nelson was such a craft.

Grant sailed from Gravesend to Portsmouth to join a convoy and completed his provisions. When all was loaded, the vessel was very low in the water so that some of the crew thought she was unfit for the voyage. Schanck inspected the ship and gave approval but the carpenter still managed to escape the sailing.

On 17 March they set sail and after a few days the Commodore of the fleet order the Lady Nelson to be towed as she was slower than other ships due to the heavy load. She was ordered to join the West Indies Fleet at Falmouth. On 23 March the weather deteriorated and Grant ordered to let go the hawser and they continued on their own. During a gale they were chased and fired on by an English frigate that thought they were Spanish and later apologised.

They continued alone and found that they had leaks topsides causing damage to sails. With fair weather, Grant made the crew air their bedding and clothes in order to keep the crew healthy. Passing the Canary Islands, they stopped for a couple of weeks in the Cape Verd(e) islands (a Portuguese possession) , where they filled up with water, purchased a bullock for fresh meat and repaired one of the keels damaged in the heavy weather.

They sailed close to Rio Janeiro (sic) but decided they had enough water to avoid stopping. They set off for the Cape of Good Hope and fell in with a captured Spanish ship, which did not have books or charts and did not know where they were. They suffered damage to the main keel in heavy weather and sailed into Table Bay for repairs from the naval yard. Fastenings of the keels were changed so that bolts did not go right through the planks and so weaken the wood.

With repairs completed, Grant moved the ship to Simon’s Bay (Simonstown) as it was more sheltered. They remained over three months at the Cape “for a convenient season to make passage to New Holland”. Grant explored the colony, which had not long been in British hands. He hoped that the “late mild and just Government had left a favourable impression of the British character on the minds of the discerning part of the inhabitants” but feared that “democratic principles” had “been instilled into the Dutch by their French neighbours”. He saw little poverty in the Cape and observed that the Dutch were indulgent to their decayed and aged slaves. He noticed the difference in races due to the climate between the “Hottenots, Boschmen and Caffres”.

Whilst at the Cape, Grant received orders from the Duke of Portland, Secretary of State, “to search for the Strait which separates Van Diemen’s Land from New Holland and to make my passage, if possible, through it”. He recruited a doctor and carpenter and set sail on 7 October.

Grant sighted land in early December, around the present day South Australia – Victoria border. He named features that he passed: Capes Northumberland and Bridgewater after English dukes, Mount Gambier, Portland Bay (after another duke) Cape (Albany) Otway after a naval captain, Cape Liptrap after a London friend. He passed Wilson’s Promontory, named by Bass and identified on Sir Joseph Banks’ chart, and named the Glennie Islands close to the Prom. He reached Port Jackson (Sydney Town) on 14 December.

Grant gives a description of Sydney “larger and more respectable” than he had imagined. He delivered the stores from the lady Nelson and the crew were paid “a very handsome compensation” but Governor King had no instructions to pay Grant. The Admiralty had appointed him to take command of the HMS Supply on arrival but he found it “laid up as a hulk and unfit for the sea”. After arriving in Sydney, Grant had no money and no job. Governor King offered him command of the Lady Nelson but at lower than naval pay rates. In addition, being detached from naval service would but promotion out of reach. Governor King promised to take steps to avoid that. Grant was also concerned that only two of his original crew signed up with most of the rest being convicts. He was not impressed by these and had to resort to lashes to instil discipline.

King had little choice as there was no other officer experienced with sliding keels. Grant, however had no other options and no money.

Governor King allocated Garden Island to raise vegetables for the crew and Grant put Dr Brandt, whom he had brought from Cape Town, to take charge. He had a boat stolen and pursed this for some time up the Hawkesbury.

King’s instructions were to ascertain the extent of Bass Straight. He ordered the removal of some guns from the Lady Nelson to minimise government loss should the vessel not return. This did not impress Grant but he had four privates from the NSW Corps plus Ensign Barrallier as surveyor and a botanist, Mr Cayley. He also had two natives. Barrallier was a French born engineer who served in NSW from 1800-183. He returned to the British Army through the wars with France and rose to became a brevet major in 1830 and a brevet lieutenant-colonel in 1846. He died on 11 June 1853 at his home in London, at the age of 80.

He set sail on 6 March and after exploring Jarvis Bay, arrived at Wilson’s Prom on 20 March. He sailed on to Westernport and named the island at the entrance Snapper Island due to the shape. This had been previously named Phillip Island by Bass. He then discovered a pleasant, sheltered island with rich soil that was excellently adapted for a garden. This he named Churchill Island after John Churchill, Esq of Dawlish who had supplied “a variety of seeds of useful vegetables, together with the stone of peaches, nectarines and the pepins or kernels of several sorts of apples with an injunction to plant them for the future benefit of our fellow-men, be they Countrymen, Europeans or Savages”. He found holes of a large size, the burrows of an animal.

Grant’s men continued to explore Western Port, looking for water and also Snapper (Phillip) Island where the trees were not as large as on Churchill Island. On 28 March he returned to Churchill’s Island “not having found any place fitter for the purpose” to clear ground for a garden. His men burned a space of 20 rods (just over 100 metres) and felled the larger trees. Grant’s men cleared the spot he had laid out for the garden but only had a coal-shovel. On the advice of Captain Schanck, Grant had brought gardening tools from England but these had been taken into the government storehouse in Sydney where it was not easy to get them out again. However, the soil was easy to work and the shovel served the purpose.

Sleeping in a hut on the cleared ground, one of the men was awakened by a “bandicoot-rat” gnawing at his hair.

Grant recorded that he sowed several sorts of seeds, together with wheat, Indian corn, and peas, some grains of rice, and some coffee berries. He did not forget to plant potatoes. With the trunks of trees felled, he raised a blockhouse 24 feet by 12, “which will probably remain for some years”. He recorded that “I was anxious to mark my predilection for this spot, on account of its beautiful situation, insomuch that I scarcely know a place that I should sooner call mine than this little island”. Round the “skeleton of this mansion house” he planted stones and kernels of the several fruits I had brought out”.

Grant charted most of Westernport and then proceeded to chart the coast between Westernport and Wilson’s Promontory. He had been instructed to chart all of Bass Strait but the weather was unsettled, wet with sudden gales which prevented sailing close to shore which is necessary to chart unknown coasts. He resolved to head back to Sydney where he arrived on 14 May, 1801.

Governor King seemed pleased with the outcome. Grant was then ordered to the Lieutenant Governor, Colonel Paterson to the Hunter River. There Barrallier continued to survey and they took on board timber and forty tons of coal. They arrived back in Sydney on 25 July. Grant records that his major object having been achieved there was nothing to keep him in the colony.

On 9 November 1801, he set sail on the Anna Josepha, an old Spanish brig captured off Peru and sent to Port Jackson. They rounded Cape Horn and stopped at the Falkland Islands. On reaching Tristan da Cunha, they were becalmed and Grant took passage on an American ship the Ocean hoping to get to Cape Town more quickly. He reached there on 1 April 1802 and took the final leg of his journey on HMS Imperieuse reaching England.

Grant returned to naval duties and reached the rank of commander. He saw action in command of HMS Hawke. In 1805 and was badly wounded. He retired with a pension but later returned to naval service in command of the Raven and Thracian. He died in 1833 aged 61.

Governor King appointed Lieutenant John Murray to the Lady Nelson and ordered him to complete the charting of Bass Strait. On 8 December, he returned to Churchill Island and recorded “A.M. I went in the gig to Churchill’s Island and there found everything as we left it–I mean the remains of our fires and huts; the wheat and corn that Lieutenant Grant had sown in April last was in full vigour, 6 ft. high and almost ripe–the onions also were grown into seed; the potatoes have disappeared–I fancy that the different animals that inhabit the island must have eaten or otherwise destroyed them. I regret not having time or men to spare to clear a large spot and sow the wheat already grown, as the next crop would be large. I never saw finer wheat or corn in my life, the straw being very near as large as young sugar-cane. The next day “the party caught and shot 5 pairs of swans, out of which 3 pairs were young, and brought on board alive, the others were old and we made some fresh meals from them; they also brought on board a pair of young geese which however are very scarce, but few parrots–the ducks are as shy as ever…At 3 P.M. sent the second mate to Churchill’s Island to cut down the wheat on purpose to feed the young swans with it, at sundown they returned on board with it in the whole perhaps a bushel in quantity with a good deal mixed with oats and barley all fine of their kind–some potatoes were also found and 2 onions”.

Murray continued to chart Bass Strait and Port Phillip, completing the task originally assigned to Grant. He was the first European to enter Port Phillip Bay. In April 1803 Governor King received a dispatch informing him that the Navy Board had refused to give Murray a full commission because he had given false details of previous service in England and had not served the required full six years as had claimed. Reluctantly, King was required to remove Murray from command of the Lady Nelson; though he retained a good opinion of him, as evidenced by his later letters to Joseph Banks. Murray returned to England in the Glatton in May 1803.

There is little record of Murray’s later life: he appears as the author of several English coastal charts in 1804, 1805 and 1807, which suggests he succeeded in repairing his reputation with the admiralty, on whose behalf the maps were made. His date of death is unknown.

European History

John Rogers – 1854 to 1860

In 1854 John Rogers acquired the pastoral lease for the Sandstone Island Run and became a squatter (the accepted term at the time and since for a lessee of a pastoral run is a squatter).

The run originally comprised Sandstone, Elizabeth and Churchill Islands. Evidence suggests that Elizabeth Island became a run in its own right in 1855, and Churchill Island in 1860. Until 1863 Rogers paid £10 per annum for the privilege of de-pasturing each separate Run. Thus Sandstone and Churchill Island cost Rogers £10 jointly till 1860, and £10 each from 1860-1863. From this point onwards the Churchill Island run cost Rogers only £2.10.

How early Churchill Island was used by Rogers is difficult to pinpoint. His pastoral returns for the island in 1854 and 1860 show no stock de-pastured on the island, but parliamentary debates in 1861 record that Rogers was illegally cultivating his island pastoral runs, including Churchill Island against the terms of his de-pasturing licence. Georgiana McHaffie’s diary suggests that Rogers continued to cultivate illegally, despite the notice he had attracted in parliament. How long Rogers used Churchill Island for agricultural purposes is unknown.

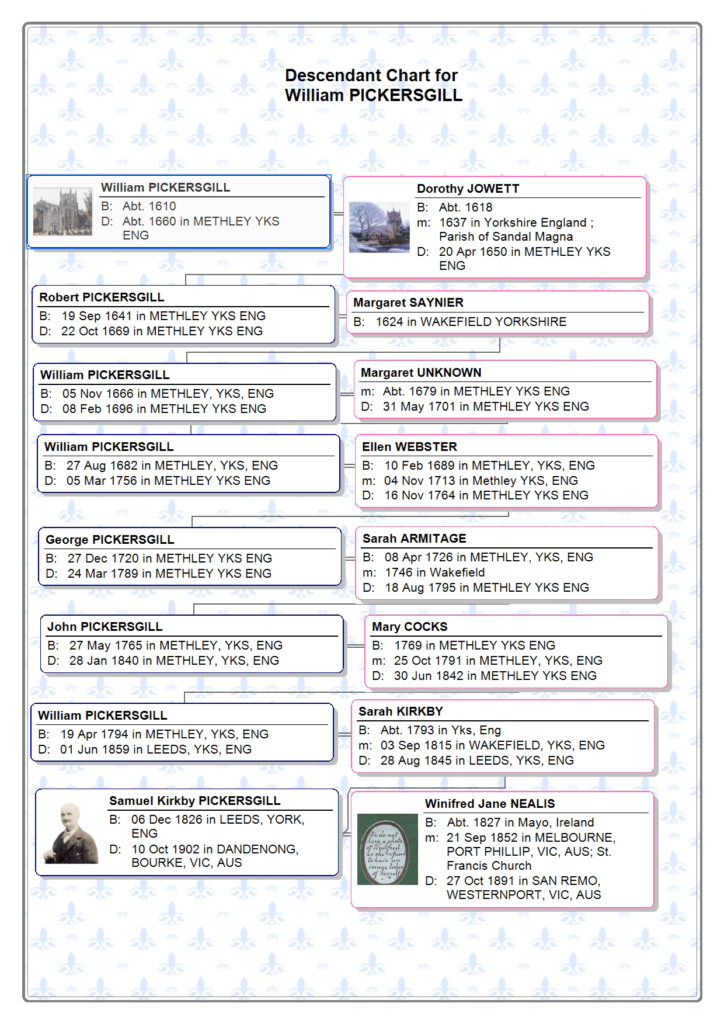

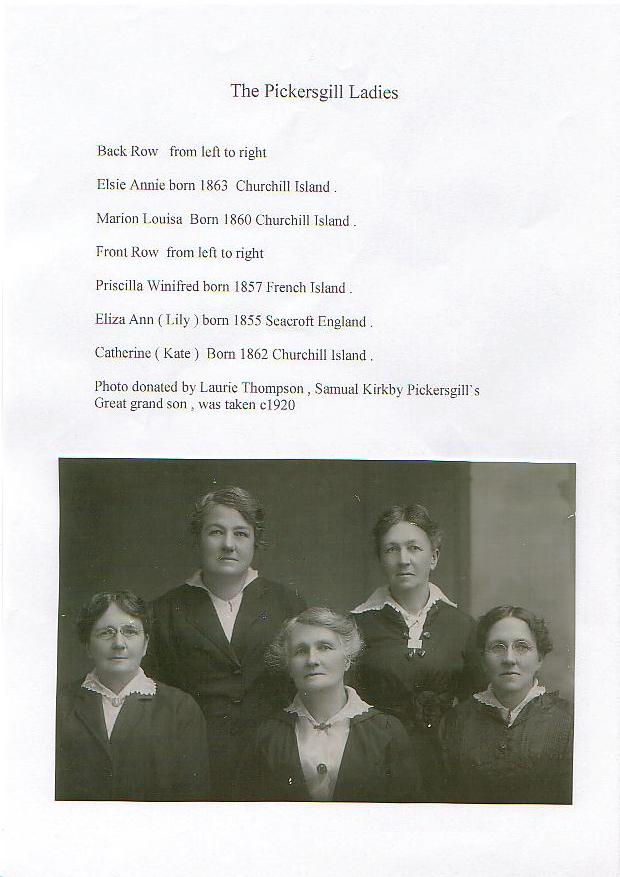

Pickersgill Era – 1860 to 1866

The first European settlers of Churchill Island arrived via sailing or row boat from French Island in 1860. Samuel Pickersgill had recently been released from indenture as a farm labourer and together with his wife Winifred and their three children, took up land on Churchill Island.

It is difficult to imagine the remoteness of Churchill Island at this time. The only other settlers in the vicinity were the McHaffies who lived at the western end of Phillip Island some 25 miles to the west and the small port of Griffiths Point (now San Remo) to the east. Both of these neighbours could only be reached by sail or row boat. Nevertheless, Winifred went on to have a further five children and to support her husband to build a small dwelling and vegetable garden which sustained the family for their six years of habitation on the Island.

The Pickersgills never legally owned Churchill Island and moved to Griffiths Point (San Remo) a few years after the freehold was sold to John Rogers.

John and Sarah Rogers Era – 1866 to 1872

John Rogers became the legal owner of Churchill Island on January 15th 1866 for the sum of two hundred and ten pounds. Rogers first built a cottage for his family and later another adjoining the first. The fact that these two cottages still stand today is a testament to his building skills and hard work.

John and his wife Sarah went on to create a vegetable garden, an orchard and planted rows of trees for shelter beds. This pioneering farming family established crops and not only maintained themselves but supplied wheat and vegetables to the Melbourne markets.

John Rogers, and his family did not remain long on Churchill Island after its purchase. The island was sold in 1872, but Rogers had already removed to Brandy Creek near Buln Buln sometime around 1869 and 1870 under the terms of the Amended Grant Act of 1869, having selected land there on the recommendation of his Westernport neighbour James Hann. In purchasing Churchill Island Rogers had been able to make his investment in the property secure, but the island was too small to make a comfortable living.

The freehold was eventually mortgaged to JD McHaffie who subsequently sold it to Samuel Amess. The Rogers left a well-established and prosperous farm, orchard and still-standing dwellings.

Amess Family Era – 1872 to 1929

Samuel Amess bought Churchill Island in 1872 when he was at the height of his career as a successful stonemason and builder. He had been appointed Mayor of Melbourne in 1869 and was responsible for some of the most significant building works in Melbourne during the prosperous years after the gold rush of the 1850s.

Amess bought Churchill Island as a summer retreat for his family after hearing about its abundant produce. During his time on the Island he built the substantial homestead “Amess House” and, as a member of the Victorian Acclimatisation Society, introduced rabbits, quails, and pheasants. He also established a fold of and West Highland cattle which, as a Scotsman, were to “maintain fond memories of the land of his birth”.

Samuel Amess brought the same energy and enthusiasm to Churchill Island as marked his career in Melbourne as a builder and Alderman. He grew onions, extended the orchard and grew many more trees including some which today are included on the National Trust Historic Trees Register such as the majestic Norfolk Pine outside the homestead, the Olive and Mulberry trees as well as all of the native Moonahs.

Churchill Island passed through two further generations of the Amess family, retained as a holiday farm and home to a retinue of farm managers and domestic servants who maintained the property for the pleasure of the squire. The island was eventually sold in 1929.

You can read more about Samuel Amess here: Cr Samuel Amess (1826-1898): His life and times

Gerald Buckley Era – 1929 to 1935

In 1929 another Western district farmer, Gerald Neville Buckley heard that a small Western Port island was for sale. A bachelor, he was known as a kindly man who had been born into a wealthy family but never lost the common touch.

An absentee owner, Buckley employed the Jeffery brothers, Bob and Ted to run the property and a flurry of building activity commenced. A dam was dug out, a windmill was erected, and a milking shed built to accommodate the new milking machine. By this time the island was supporting a dairy herd of some 80 Ayrshire cows. Bob and Ted, with the help of Harry Cleeland laid a track across the Island and a crossing to the mainland which was marked with a guide post indicating the tide level. When this was visible, a horse and cart could be driven across and it was by this route that the milk and cream was transported to the mainland.

After diligently building the farm into a prosperous business, the Jeffrey brothers were promised by Buckley that Churchill Island would be passed to them on his death. Unfortunately within a short time, Buckley died and within a few months the property, including all the beautiful furnishings was sold.

Dr Harry Jenkins Era – 1936 to 1963

Dr Jenkins was an adventurer and counted road car racing, hill climbs, motor cycles, crocodile shooting and adventurous travel amongst his favourite pursuits.

Jenkins introduced many innovations to the farm including a tractor to replace the working horses and a wind powered generator to supply electricity and in 1959, a bridge to connect the island to the mainland. He introduced Hereford cattle, beehives, a flock of turkeys (which always seemed to mysteriously diminish around Christmas) and water tanks to supplement the dam supply.

After Harry’s wife Alice died, Sister Margaret Campbell became the driving force of the family. Between her duties in caring for Ted, she managed to run the house and farm and act as hostess to the many guests that visited Ted and Harry when they entertained on the island.

Ted died in 1960 and Harry three years later and ownership of the island passed to their lifetime carer, Sister Margaret Campbell.

Sister Margaret Craig Campbell – 1963 to 1973

Sister Margaret, or “Aunt Jimmy” as she was known to the locals, continued on the island running the farming business. Born into a farming family, life on Churchill Island was no hardship for Sister Margaret. During her 40 years on the island, she not only provided the mainstay for the Jenkins’ family, she was the driving force behind the farm. To help her she re-engaged Ern and Eve Garrett who had been employed by Dr Jenkins before the war as farm managers.

Entering her 60s and with a debilitating disease, Sister Margaret finally had to put the property up for auction in 1973.

Sister Margaret is fondly remembered by her neighbours and friends as a caring and energetic woman who truly cared for Ted Jenkins and her precious Churchill Island.

Into Public Hands – 1973 to Present Day

Churchill Island was bought at public auction by Mr. Alex Classou of Patra orange juice fame in 1973. Mr. Classou had a vision to turn the island into a horse stud. He employed Bruce and Margaret Blenheim as managers to set up the property for this purpose. Classou was approached by Sir John Knott, chairman of the newly formed Victoria Conservation Trust, and asked if he would sell Churchill Island to the government, which he did in 1976.

Central to the acquisition of Churchill Island by the Victorian Government was Sir Rupert Hamer and the Victorian Conservation Trust (now Trust for Nature). After its purchase the trust had little money left for restoration and relied on its auxiliary, the Churchill Island Restoration Group to raise funds and build sponsor support to realise small restoration projects. In 1982 CIRG merged with the Friends of Churchill Island Society (FOCIS) and worked closely with Churchill Island farm manager Carroll Schulz to restore and preserve Churchill Island’s heritage.

Highland Cattle were first brought to Victoria by Lord Glengarry in 1841 when he landed at Port Albert with his clan. In 1872 Samuel Amess senior imported four head of black highland cattle direct from the Isle of Skye to establish a “fold” of the cattle on Churchill Island. The cattle increased until a fold of over 30 head flourished here. The FOCIS Highland Cattle Fold, Churchill Island, was established by the Society in 1986. With the ready co-operation of the department of Conservation Forests and Lands, Dandenong Region, a grazing permit was issued to FOCIS. This has also become a community project involving local schools.

Building on the tradition of volunteer labour initiated by Dr Jenkins, the care of Churchill Island was enthusiastically taken up by a team of people both local and more distant. In the years following public purchase, if it were not for the dedication of these volunteers much of the historical significance of the island would have been lost.

In 1996 Churchill Island was incorporated into the holdings of the Phillip Island Nature Park (PINP). In the decade following, a number of major restoration works were completed including bringing the homestead back to an original form, replacing Dr Jenkins’s bridge (which had been infested with marine worms) with a concrete bridge and the construction of a visitor centre and café. The gardens were restored and a working farm was now possible as farm management and labour was now able to be funded by the PINP.

Churchill Island Today

Churchill Island is a small island almost connected by mangroves to Phillip Island’s eastern flank, surrounded by the mudflats and waters of Western Port.

Churchill Island is an ideal place to visit with family or friends to spend an hour or two taking in the stunning views, the historic ambience and seeing the West Highland cattle, Suffolk sheep and the animal nursery which is a great favourite with the children. Visitors can have a ride in the coach, meet Sophie the Clydesdale, see the ducks and chickens and the wild Cape Barren geese and other native birds.

Churchill Island is full of wonders for everyone with an historic homestead, a charming garden and rustic outbuildings all within a working farm. Farm demonstrations including sheep shearing, whip cracking, working dog and cow milking, are held each afternoon.

The Churchill Island Cannon: History and Mystery

David Maunders

The Myth

The cannon came from the CSS Shenandoah, a warship of the Confederates States in the American Civil War. During the ships’ stay in Melbourne in 1865, the cannon was presented to Samuel Amess in gratitude for his role in the hospitality offered to the officers. After Amess built the house on Churchill Island, the cannon was located there.

This version of events was part of the Amess family history “handed down by word of mouth” (Ian Amess, letter to Robert Marmion, 15 March 1982, VCT Cannon File part 1). It was known to the private owners and to the Victorian Conservation Trust when it became responsible for Churchill Island in 1977. Shortly after the purchase of the island, the VCT arranged for the restoration of the cannon by the Flinders Naval Base, when it is assumed that the break in the barrel and its repair occurred (letters of 10,20 October 1977, VCT Cannon File part 1). From this time until 1983, the VCT, largely through its Executive Director Colonel Ian Wilton and his Assistant Director, Ross Lawson, undertook extensive correspondence to identify the history of the cannon. They were certainly spurred on by the American Civil War Round Table of Australia, whose members had undertaken extensive research into the Shenandoah and the cannon and concluded that the cannon could not possibly be from the Shenandoah (Report of 1979; Letter of 17/8/1981, VCT Cannon File part 1). The VCT was reluctant to accept this. The ACWRTA accused the VCT of misleading the people of Victoria by claiming that the cannon came from the Shenandoah and of being more concerned with losing a tourist drawcard and having to withdraw brochures than putting the record straight 4 February, 1982, VCT Cannon File part 1).

The Round Table’s arguments were based on the following facts:

- The Ordnance carried by the Shenandoah did not include 6 pounder cannon, the smallest being 12 pounder signal guns;[1]

- The guns were supplied from Britain and had British government Ordnance marks;

- Detailed lists were kept of articles removed from whalers captured or sunk; only 3 ships had guns and these were sunk with the ships;

- There is no record of a council reception or report of the presentation to Amess;

- For a British subject to receive arms from a foreign power was illegal.

The Round Table wrote to the premier, minister, leader of the opposition and the matter received attention in the press. These facts did not impress the VCT. Carroll Schulz, then head ranger of Churchill Island wrote to the Round Table that the Trust was still researching the origin of the cannon.

“If the Trust accepted every claim such as that of your society, without question and without exhaustive research of its own, it would be lacking in its duty to the people of Victoria” (13 February 1982, VCT Cannon File part 1).

Archives contain several very long letters from Carroll Schulz defending the Trust’s reluctance to accept the evidence that the cannon did not come from the Shenandoah. His argument is generally based on the strength or the oral history. We can only conclude that they were willing to abandon a good story.

The Trust did conduct exhaustive research but still did not put the record straight. Consequently Churchill Island Guides, in many cases unwittingly, continued to deceive the people of Victoria and from further afield almost to the present day. The brass plate indicating the Shenandoah origin and attached in 1964, was finally removed in 2021.

The History: The Shenandoah

The voyages of the Shenandoah were documented by the ship’s log and from journals kept by a number of officers (Captain Waddell, Surgeons Lining and McNulty, Lieutenants Hunt, Chew and Whittle). A significant number of accounts drawing on these and other sources have been published in the USA and in Australia[2]. In addition, the there are the ship’s log and journals of officers Lining and Chew, with those of Hunt and Waddell which were published). More recently (2007), retired Melbourne solicitor Henry Gordon-Clark completed a doctoral thesis at Monash University, “The last gun in defence of the South” : the story of the CSS Shenandoah and her cruise around the world in 1864-1865.

The Shenandoah was a steamer clipper (a fast sailing ship with a steam engine) built on the Clyde in Scotland in 1863 under the name of Sea King. She was purchased by the confederate agent under an assumed name and left London in October 1864 with a registered destination of Bombay but actually for Madeira. There she came under the command of Captain James Waddell, a native of North Carolina and graduate of the United States Naval Academy who had left the US navy at the outbreak of the Civil war. In Madeira she met the Laurel which left Liverpool at the same time carrying guns, ammunition, stores and ship’s officers. These were transferred and the Shenandoah headed south on 20 October but with a crew only between 42 and 47, approximately one third of the size of its normal complement. Her purpose was to strike at American whaling ships in the Behring Sea. Whale oil was used for lubrication in industry and whale bone had a variety of uses and it was considered that damage to the whale industry could be a blow to the US economy. On her way to Melbourne, the Shenandoah captured nine ships.

On 25 January, 1865, the Shenandoah anchored off Sandridge (Port Melbourne). She came to Melbourne to refuel, take supplies and land prisoners. A storm had caused damage to the propeller shaft and the supply vessel John Fraser (owned in South Carolina) was expected with a cargo of coal from Liverpool. Neutral ports (such as Melbourne) were only allowed to provide supplies sufficient to carry the vessel to the nearest port of her home country and a ship of war was expected to stay no longer than 24 hours.

The arrival of the Shenandoah in Melbourne caused a sensation. Small boats surrounded the anchoring ship and over 7,000 people visited the ship the day after her arrival. This continued with a peak of 10,000 in one day with many refused through lack of space. Visitors seriously interfered with repairs so finally the captain refused to have any more. The Argus and Age newspapers covered the visit extensively with the Argus being sympathetic to the Confederate cause and the Age more opposed. Governor Darling gave permission for repairs to be made on the Government slip at Williamstown and the Shenandoah was towed there on 4 February leaving the officers to continue the round of social events. E Chambers & Co, responsible for the repairs, advertised in the Age that visitors would be charged six pence and proceeds would be distributed among benevolent institutions in Melbourne.

Hospitality was boundless. The railways provided free passes for the officers and invitations to dinners and balls poured in. Major entertainments included dinner at the Melbourne Club, attended by sixty Victorians including some judges and an invitation to Ballarat made by local expatriates. In Ballarat, the officers were shown the mines and attended a civic Ball meeting a large number of pretty women. In Melbourne, they paid visits to the parliament, Kew Insane Asylum and attended many private dinners.

Not all Melbournians were sympathetic to the Confederate cause and Lieutenant Hunt records a fight breaking out at Scott’s Hotel but with no serious results. In addition, the US Consul William Blanchard demanded that the Shenandoah be seized as a pirate. When no action was taken, he pressed the Governor to arrest a cook named Charley who was a British citizen on the evidence of former pressed sailors from the Shenandoah. (The British Foreign Enlistment Act prohibited citizens from enlisting under foreign flags). Fifty policemen (Surgeon Lining records two hundred) were sent to Williamstown, surrounded the dock and arrested Charley. Work on repairs was stopped until public meetings protested against the government action. The ship was finally refloated, took on provisions and sailed from Melbourne on 18 February. However, forty-two men stowed away and signed on as crew members. Advertisements had been placed in newspapers by a mysterious Mr Powell who evaded warrants for his arrest.

The Shenandoah sailed on to the Behring Sea and captured nearly another thirty Union ships. She inflicted damage to US shipping of over $US1.3 million (in contemporary values) but did not take one human life. She continued to do so for four months after the official end of the war and, on learning of the demise of the South, sailed to Liverpool where the crew disappeared. Captain Waddell stayed in England until 1875. The Shenandoah was sold to the Sultan of Zanzibar but was wrecked in 1879 (Stanley F Horn, Gallant Rebel, Rutgers University Press, 1947). Seven years after the end of the war, an international tribunal investigated claims that Britain had harboured Confederate raiders and awarded the United States $US15.5 million (of which Noble estimates that 3.8 million related to the Shenandoah) (John Noble, Port Phillip Panorama, a maritime history, (Some Ships that Passed) Melbourne Hawthorn Press, 1976. VCT Cannon File part 2).

The Mystery: 1. How and why was Samuel Amess presented with the cannon?

If we overlook the overwhelming evidence that the Churchill Island cannon was not part of the armament of the Shenandoah or one of the captured ships, we are faced with the mysteries of why there is no record of the presentation, why it was given to Amess and how it was actually given into his charge.

Descendent Ian Amess argues “that there were no press reports of the presentation is not surprising considering the international situation of that time”. Whilst that may be true, it is surprising that there is no record of Amess’s hospitality in journals of the officers. Amess was not mayor at the time (he later served from 1869 to 1870) and does not seem to have been a prime mover of the Melbourne Club dinner. However, Cyril Pearl wrote (possibly following Amess tradition) that “one of Waddell’s most enthusiastic hosts was Samuel Amess…” (Rebel Down Under, 1970). Many private individuals gave dinner invitations, so what was the hospitality that was so significant to warrant the gift of the cannon? Was he the mysterious Mr Powell, involved in the illegal recruitment of sailors? Given his background (builder and stonemason, gold miner, councillor) this seems unlikely, though this idea did occur to archaeologist William Wright (Letter of 22 October, 1982, VCT archive – Cannon Part 3).

Assuming that the cannon was given to Amess , how did it get into Amess’s possession given the logistics of moving it and the security surrounding the illegal enlistment, including the surrounding of the vessel on the Williamstown slip? Wilson P Evans, Williamstown City Historian, wrote:

In 1950, I carried out research in Australia and overseas in an attempt to ascertain if Captain Waddell presented this gun to Samuel Amess during the stay of the raider in Port Phillip. I found no record that there was any transaction between Amess and the Shenandoah in respect to a gun or guns. The only time it would have been possible to lift the weapon out of the raider was when she was hove to outside Port Phillip Heads. I consider such a transfer unlikely since I hold the pilotage records of the Shenandoah. (Letter of 5 July, 1982. VCT archive – Cannon Part 3).

Moving a cannon around in the 1860s was not easily accomplished in a clandestine manner. Surprisingly, Wilson’s research in 1950 did not move the then owner Dr Harry Jenkins from the Shenandoah origin as (an accepted fact of life” (Letter from ABD Evans 27 May 1982 VCT archive – Cannon Part 2).

John Cleeland, who build Woolamai House around the same time that Amess built his house on Churchill Island, claimed that Captain Waddell had given the cannon to him. (This was written in an account by a grandson). There is a probable connection between the confederate officers and Cleeland who ran the Albion Hotel in Bourke Street. The Murchison Times 18 February 1916 wrote “The Shenandoah officers were feted by the Melbourne Club. They put up at Cleeland’s Albion Hotel Bourke Street. He named his grey racing filly Shenandoah”. Whilst this is much later than the event, Cleeland’s racehorses are a matter of record. He did give hospitality but this in itself does not give weight to the cannon’s origins.

Amess was almost certainly given the cannon by John Cleeland. In a letter printed in the Australasian, 9 March 1907, his granddaughter Marjorie wrote “We have a large cannon in the orchard which belonged to the American war-ship Shenandoah and was given to my grandfather by a friend”. The friend was almost certainly John Cleeland.

The Mystery: 2. Why did Amess deceive people about the origin of the cannon?

If the cannon did not come from the Shenandoah, why did Amess say that it did? Family tradition argues that it was because it came into his possession illicitly. However, the story became a tradition, which many were reluctant to disbelieve. Ross Lawson wrote to American cannon expert Edwin Olmstead: “There were too many people who were alive and knew Samuel Amess who supported the story for it to be completely wrong” (Letter to Olmstead, 1 February 1983, VCT archive – Cannon Part 3). This is an incredible admission. There is little doubt that Amess told the story but that is not the same as it being true..

That leads us to the major mystery of the origin of the cannon.

The Mystery: 3. What was the origin of the cannon?

The VCT tried hard to find out the origin of the cannon. Its officers approached every expert they could identify in Australia, the UK and the USA and commissioned their own local expert, Tony Dunlap, to report on the origins of the cannon. The cannon was weighed, measured and photographed. Identifying marks F RECK, 38, 860 were interpreted. F Reck was assumed by many to be the founder and an attempt to identify the foundry through historians of the Reck family in the USA proved fruitless. In addition 38, was accepted as the piece number (though some thought it might be 1838 as date of manufacture) and 860 thought to be the weight (more or less confirmed by weighing) but some thought it might be 1860.

Experts agreed on very little other than the piece was not of British manufacture. Let us consider the views of the major contributors.

- The American Civil War Round Table researchers Duff and Marmion concluded that the cannon was one of the four six pounders left behind when the Westernport Settlement was abandoned in 1827 (sic) (Report of 17/August 1981, VCT archive – Cannon Part 1). This was the establishment of Fort Dumaresq on the cliff at Rhyll, established from fear of the French and the Corinella settlement. This theory was rejected by Ray Fielding, Curator of Arms at the Melbourne Science Museum. He argued that firstly all guns were returned to Sydney when the settlement was abandoned in 1828 and secondly that six pounder cast iron guns in British service were six or eight feet long and weighed 17 or 22 hundredweight, larger than the Churchill Island cannon (letter of 18 March 1982, VCT archive – Cannon Part 1). This was also the conclusion of Dunlap in his report (Report, 1982, Appendix G).

- Tony Dunlap. Dunlap, a local armament expert, was commissioned to investigate the origin of the cannon. His report (1982 in CI Archives), according to the VCT, was inconclusive (perhaps not reaching their hoped-for conclusions) and argued that the cannon was of Confederate origin. Dunlap confined his research to cannons from North America and reached his conclusion because arms production in the South was somewhat chaotic and they he could not find any other answer. Fielding suggested that it was more reasonable to conclude that the cannon was produced in America in the mid 19th century. It is interesting to note that American experts do not suggest an American origin. Confederate origin does not strengthen the Shenandoah connection as her arms were supplied from Britain.

- Ray Fielding, Curator of Arms at the Melbourne Science Museum, concluded that the gun was “consistent with the type found on merchant vessels of the period, the breeching loop above the cascabel knob is an indication that it was made as a ship’s gun”.

- Edwin Olmstead, an American expert on muzzleloaders, contributed several letters. They are long and confusing, though in one he states: “I have neither seen nor heard of any piece even remotely resembling that at Churchill Island…” At one point he suggested it might be a hoax. (Letter of 2 July 1982, VCT archive – Cannon Part 1).

- William C Wright, Historical Archaeologist, Department of Archives and History, State of Mississippi. Wright argued that the tube was Prussian and the F Reck signified the reign of Frederick IV, 860 was the date of casting and that the “cheeks and trunion caps are definitely of European origin” (Letter of 22 October, 1982, VCT archive – Cannon Part 3). No arms manufacturer F Reck has been found, in fact the only company by that name appears to be F. Reck & Co, an equipment and food supplier for ships and emigrants, founded by Friedrick Reck on 15 September 1848 in Bremen. On 1 January 1854 he moved into the shipping business, adding ‘private insurer’ at the same time. By 1863 his fleet consisted of eight sailing ships. So the question might be asked as to whether this gun may have come from one of his ships or provided to a ship under his insurance. There certainly was a gun etc manufacturer named Reck which appears in various collectors’ forums. The Imperial War Museum in England has at least one Reck revolver.

- The swivel gun theory. Sam Happe, curator of the Churchill Island Museum 2020-2021 provided information to the historic gun registry and found several references to a proposed modification to fit a swivel gun on the bow of the Several papers of the time reported plans to mount swivel guns forward. The Mount Alexander Times in a report on 31 January 1865 reported Captain Waddell ‘request permission to alter his vessel in such a manner as to permit of her mounting swivel guns forward, or in other words to render her more formidable as a cruiser chasing the merchant ships of the enemy’. Then on 20 February, it reported ‘nor do we have any proof of the rumor that the Shenandoah has obtained all the necessary appliances for mounting a forecastle swivel gun, which will be conveyed to sea in another vessel with engineers to fit it up’. This latter was probably fostered by an article in the Bendigo Advertiser reported on 18 February ‘It is rumored that the Shenandoah has obtained all the necessary appliances for mounting a forecastle swivel gun, which will be conveyed to sea in another vessel with engineers to fit it up. If it is possible to effect this no doubt it will be done’. Then on 4 March 1865 the Melbourne Leader reported ‘The last rumor with regard to the Shenandoah is that she is lying at anchor in some bay on the Tasmanian coast, and that artificers, honorably engaged by Captain Waddell during his stay in this port, are busily engaged in strengthening her, and mounting swivel guns fore and aft, so as better to fit her for her piratical work’.

It is possible that Waddell obtained the cannon in Melbourne with the intent to fit it but found it impossible to get on board. He then gave it to Cleeland. There is no evidence for this, it is pure conjecture. The cannon was also significantly obsolete in comparison to the Shenandoah’s other armament.

It seems likely that the gun came from a merchant ship. Ross Lawson suggested that it might have come from Captain Corbett’s supply ship (the Laurel or the John Fraser?) and as it was outdated, to be used for barter. (Letter of 26 April, VCT archive – Cannon Part 11982). To confuse matters more, Carroll Schulz said that he had been told that there were two cannon and that a larger one had been taken to Melbourne. When fired by Dr Jenkins, it “lobbed a ball on French Island” (letter Ian Wilton, 19 February 1982).

Research undertaken by Churchill Island restorer Jeff Cole, indicates that mid century 6 lb cannon were much smaller and essentially signal guns. He drew comparison with the Saker used in India.

A Guide for the Guides. What shall we tell the visitors?

The story of the cannon’s Shenandoah connection is a myth. There is general agreement that the gun did not form part of the ordnance of the Shenandoah and no record of it coming from one of the captured vessels. It was probably given to Amess by John Cleeland but that does not help with the origin. It is concerning that so much trouble has been given to perpetuation of the myth (since 1950 at least) in the face of so much contradictory evidence. Churchill Island is an accredited museum and both paid and voluntary staff have a responsibility to distinguish historical fact from tradition and myth. The role of guide is to enhance the experience for visitors and so there is no harm in recounting the story of Amess’s gift as long as it is made clear that it is a tradition not supported by historical evidence. Furthermore, considerable historical evidence (difficulty in getting the cannon ashore, lack of record in the prize list, lack of record in officers’ journals) argues against the Shenandoah connection. The origin of the cannon is not clear, though it seems to have been a maritime piece that was obsolete by the time Amess took over Churchill Island. Literature and displays should also indicate that the Shenandoah connection is a tradition not supported by fact.

The above summary shows some of the major outcomes the investigation conducted by Ian Wilton and Ross Lawson in the early 1980s. This was all conducted by letter (before the days of email and internet) and there are many other small contributions which do not affect the overall conclusion. I doubt if further investigation can turn up anything different but there is always the possibility of new information coming to light.

References

Documents cited are found in Churchill Island Archives:

Cannon Part 1.

Cannon Part 2.

Cannon Part 3.

Other documents cited are:

Henry Gordon-Clark, (2007) “The last gun in defence of the South” : the story of the CSS Shenandoah and her cruise around the world in 1864-1865. Ph.D Thesis, Monash University.

Cyril Pearl, (1970) Rebel down under, Heinemann, Melbourne.

[1] Oct 1864: 2x 32 pound Whitforth muzzle loading rifles 4.7 inch; 2 small guns prob 8 pounders

[2] Correspondence from the Tennessee State Library (22 November 1982) identified:

Cornelius Hunt, The Shenandoah or the Last Confederate Cruiser, New York Carlton, 1867.

Stanley Horn, Gallant Rebel, the fabulous cruise of the CSS Shenandoah, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1947.

James Waddell, CSS Shenandoah: the memoirs of Lt Commander James I. Waddell, ed JD Horan, New York Crown Publishing, 1960.

Murray Morgan Dixie Raider, the saga of the CSS Shenandoah, New York, Dutton, 1948.

In Australia, well known author Cyril Pearl published Rebel down under, Heinemann, Melbourne, 1970.

![]()